This NASA map shows lightning flashes per year per square-km. In mid ocean years pass without a lightning flash and ground strokes are even less common.

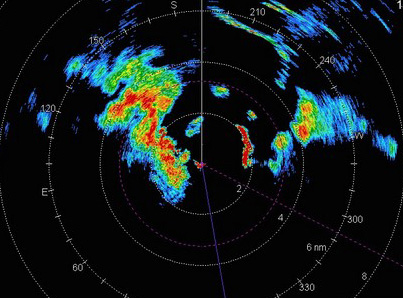

TIP: When you see a squall on radar, place a cursor on it. Check back in 5 minutes to see what direction the squall is moving and how fast (relative to your boat). If the squall is moving away, it is not a problem. If it is moving toward the center of the radar screen, you should prepare for the squall (you don't need to compensate for the boat's course and speed). Bear in mind that high winds develop as much as a mile outside the area of rain shown on the radar.

|

Depending on how big M/T Whitchallenger is, NOW might be a good time to alter course to starboard.

|